La ilaha illa Allah — cry of the believer

The following account is extracted from an early draft of The Novice. The narrator is in the heart of the Swat Valley, recovering from a debilitating bout of hepatitis and exploring the hospitality of the Pathans.

I was off to the nearby village of Miandam, where the local schoolteacher had invited me to spend a few days in his bungalow. It was set on a breezy ledge around the slopes of a gorge-like valley, overlooking plum, apricot, peach, pear, apple and walnut trees. Karim’s servant brought us vegetables with fresh maize chapattis, and a compote of fresh and dried fruits.

My host’s English was excellent, and he had a small library of contemporary books. Karim pulled out Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization and asked me about it. I tried to explain that life in his valley was so remote from Western alienation that it simply might not mean very much to him. The truth was that, while he wanted to get up to speed on Western thought, I was trying to escape it. I told him I was here in search of a more authentic lifestyle and considered his lifestyle, without television, shopping malls, reliable electricity and labour-saving devices, a great thing.

He thought I was nuts.

No, I explained, life here followed natural rhythms, and Marcuse’s intertwining of Marxist dehumanisation with Freudian repression couldn’t be less relevant.

He thought I was patronizing him. The more I enthused about the idyll of life in his village, the less communicative he became.

I strolled down the road and sat on a fallen tree trunk. A group of eight or so adolescent boys approached me, boisterous and loud. “Hello mister,” they said. “Hey, hello”

“Hello,” I said.

“What is your come-from?” asked the first one.

“No, no, no,” interrupted another. “You are America. Yes? No? America very good.”

I shook my head and said, “England.”

“Ah, you are England. England good.”

His companion punched him in the arm and said in a broad accent, “No no, not he is England. His come-from is England.” The two glared at each other, each one evidently second-guessing the memory of their English lessons, presumably delivered by Karim.

“Actually,” I clarified. “I’m English. I come from England.”

“Yes, yes,” shouted the first decisively. “Come-from, come-from!”

The two lapsed into Pushto and ended up wrestling energetically. There was much grunting and shouting, but they were ignored by the others. Another reached towards me and pulled the chain around my neck. On its end was a tiger’s eye Buddha, a birthday gift from my sister Yolanda.

“This bad,” said the young man shaking his head. “Very, very bad.” He looked grimly at it, then kindly at me. I apparently wasn’t responsible for the abomination. His companions all concurred, repeating the word “bad” over and over. They crowded around to more clearly see the false idol. The two wrestlers stopped fighting to join in the chorus.

“Why bad?” I asked, only a little uncomfortable. “It’s just a stone.”

“What is this? What for is it?” asked one, with an expression of distaste.

“It’s a Buddha,” I said. “From Japan.”

“Buddha bad,” he said. “Japan?”

I laughed. “Why bad?”

“Not Allah,” said another. “Only Allah.”

Another said, “La ilaha illa Allah.”

“Yes, yes,” said another. “Muhammad Rasul Allah.”

Several of them chanted together, “La ilaha illallah. Muhammadar Rasul Allah.” They looked at me expectantly as one of them repeated the phrase, mouthing it slowly and deliberately. They evidently wanted me to say it.

“Larillrla,” I said hesitantly.

At this their eyes lit up and each one scrambled to be the one to correct me. “La ilaha illa Allah – La ilaha illa Allah – La ilaha illa Allah.” Their excitement approached frenzy as they coaxed me. I didn’t know what I was saying, although I recognized the word ‘Allah.’ Their hormonal excitement was overwhelming – they elbowed each other out of the way as they vied for my attention.

I raised my arms to silence them. They regained control of themselves. One was nominated to be interlocutor, and stepped forward. Once I’d mastered the syllables he worked on the stress – “La ilaha illa Allah,” and soon they were crowding together again. They weren’t satisfied until I could pronounce it precisely, and kept at me for over half an hour.

Beauty is a spell which casts its

splendour in the universe

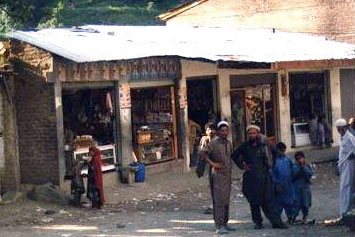

Miandam Bazaar

Meanwhile grown men passed by, smiling approvingly. Eventually, I could repeat the entire phrase to their satisfaction – “La ilaha illa Allah. Muhammad Rasul Allah.” Then they made me say it over and over until it was embedded. I haven’t forgotten it since.

They clapped me and each other on the back in great celebration. Then the one that had pulled on my chain before, once again extracted the Buddha. “Now you are Mussulman,” he said making a motion to yank it off and asking my permission with a questioning nod.

I took it gently from his hand and dropped the idol back in my shirt. He was disappointed. The others looked curiously at me, unsure whether to be concerned or hostile. How, they seemed to ask, could I have memorized the holy phrase while keeping this evil so close to my heart? “Now,” he repeated, “You are Mussulman.” He was waiting for me to agree.

I smiled uncomfortably and made to leave, pointing to Karim’s house.

The young men wandered off as I headed back. One of them turned in the road and repeated the phrase one last time, wagging his finger at me. The others laughed seriously.

Back at the bungalow I repeated the phrase and asked Karim to explain.

He smiled and said, “They did a good job. Your pronunciation is not bad. The first part means, ‘There is no lord worthy of worship except Allah.’”

“Just those seven syllables?”

He nodded. “The remainder means, ‘Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.’ It is the fundamental tenet of faith for Muslims.”

“That’s why they said I was a Muslim now,” I said.

He nodded. “You and I know that reciting a formula changes nothing. It is what is in your heart that counts. But for these boys – and for many of their fathers too – your pronunciation of the holy phrase has made you a Muslim. Yes, life here is simple – simple and ignorant.”

“But Islam is a great religion.”

“Yes, but also only one part of the greater Arabic culture.” He sat me down at his side, took up a fountain pen and placed the italic nib on the right margin of clean sheet of paper. His hand moved slowly to the left, and he swept each stroke in its entirety before lifting it and carefully inserting diacritical marks above and below, strategically moving the flat of the nib at different angles to create precise, elegant shapes. His movements were as beautiful as the marks they left behind, his face a model of concentration.

“This is the ta’liq script,” he said, raising his pen and his head together.

“There are others?”

“Arabic has six main cursive scripts, plus other ornamental and ancient forms.”

“What does this say?” I asked

“It says, ‘Beauty is a spell which casts its splendour upon the universe.’”

“I’d love to learn it,” I said.

Karim smiled. “It is a very expressive language. It is rooted in science and literature. The poetry is particularly wonderful. It loses much in translation.” He showed me how the first and last letters of each Arabic word changed form according to the preceding and following letters. Calligraphy and fine handwriting were valuable skills. We looked at some other scripts and he taught me how to hold the pen.

I stayed for a few days more, wandering a little further afield each day. As my strength returned I found I could soon walk a few hundred yards and bumped several times into one of the young men who’d ‘converted’ me. Away from the doctrinaire herd he turned out to be rather shy. We drank tea and I picked up a smattering of Pushto. Back at the bungalow, I sensed that Karim was tiring of me, and decided not to overstay my welcome.

Higher up the valley in Kalam, I knew, there were no Westerners. For so long I’d promised myself the opportunity of cultural immersion, completely away from other Westerners. Here was a perfect opportunity.

For more stories about the inhabitants of the Swat Valley in the 1970s, read The Novice by Stephen Schettini.